The book was the result of five years of work that began in 1965 with the publication of a magazine article titled “The Future as a Way of Life.” In it, Toffler posited that human society was in transition to a globalized “post-industrial” age in which the majority of human activity was devoted to services, scholarship and creativity, as opposed to agrarian and manual labor.

He went on to write two sequels, “The Third Wave” (1980) and “Powershift” (1990).

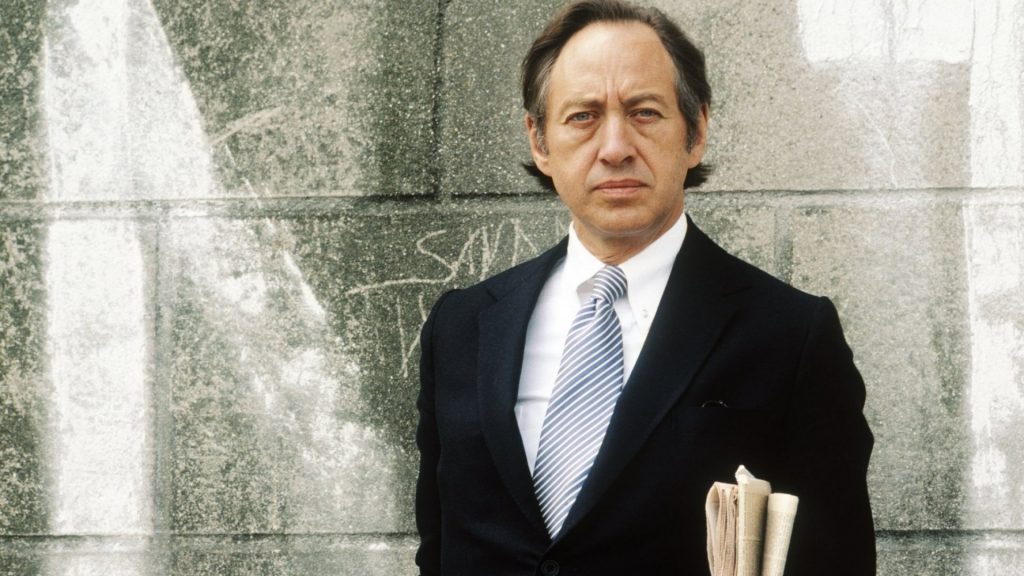

Born in New York in 1928 and raised in Brooklyn, Toffler was the only son of Polish immigrants. He began to write poetry and stories soon after learning to read and dreamed of becoming a writer from the time he was 7 years old, he told interviewers. After graduating from New York University, he worked as a newspaper reporter and editor.

He published 13 books and won numerous honors, including a career achievement award in 2005 from the American Society of Journalists and Authors.

But many of them were spot on. The overall themes discussed by Toffler and his wife, Heidi, who co-authored both of Toffler’s follow-up books, are now part of everyday life. Toffler died in Los Angeles at age 87, but the thoughtfulness and accuracy of his work lives on. When NPR asked him in 2010 why, then, he was a futurist, Toffler replied: “Because it makes you think. It opens up the questions of what’s possible. Not necessarily what will be, but what’s possible.”

Much of what Toffler wrote about related to companies, the economy, and how we do business. Here are four of Toffler’s visions for the future of business that turned out to be startlingly accurate.

1. The internet

One of the driving themes of Toffler’s work was that knowledge would become the driving force behind powerful societies–more so even than labor or materials. Toffler wrote that those people, institutions, and civilizations that failed to keep up with the pace of new information would quickly face decline. He predicted the spread of free-flowing information via personal computers and the internet, and brought the term “information overload” into the popular lexicon, a reference to the difficulty people have understanding issues and making decisions because of the overwhelming amounts of data available.

2. The sharing economy

The Tofflers believed we’d live in a society where there was no reason to own anything. Part of this was dead wrong: Heidi predicted we’d wear clothes made of paper that were disposed of after every use. But other aspects of this concept hit the mark–specifically, the idea that we’d be able to use things as needed and return them when we’re done. Zipcar and any of the ride-hailing apps fall under this category, as do Rent the Runway for wedding garb and Airbnb for apartments. It’s never been easier to call something your own–for a few days or a few minutes at a time.

3. Telecommuting

Fewer and fewer jobs today require employees to be physically present in their office. Toffler predicted this and the rise of home offices, writing that homes would one day resemble “electronic cottages” that would allow people greater work-life balance and a richer family life. Today, opinions on telecommuting policies are decidedly mixed, but there’s no denying their prevalence.

4. Businesses without formal structure

Toffler popularized the phrase “adhocracy,” a reference to a company that operates without a formal hierarchy. An adhocracy as defined by Toffler is flexible and often horizontally structured. It allows for creativity and adaptability, since employees aren’t pigeonholed into certain roles. Many startups today are adhocracies–offering roles that change based on needs and titles that wouldn’t fit anywhere on a traditional corporate ladder.

5. Future Shock

Way back in the last century, futurism was a thing that serious people followed because America was still an optimistic country. The 1970’s promised to end that but the revival in the 1980’s brought it back in vogue. The microprocessor revolution was mostly responsible, but the subsequent end to the Cold War also helped. One of the chief gurus of futurism in the last three decades of the 20th century was a man named Alvin Toffler, who wrote a number of bestselling books.

Alvin Toffler has mostly been forgotten now, but he was a big deal from the 1970’s into the new century. His two big books were Future Shock and Third Wave, in which he described how the world was changing due to a number of forces, one of which was the technological revolution that was in its infancy at the time. Toffler wound up consulting with global leaders like Chinese premiere Zhao Ziyang, Michael Gorbachev, Newt Gingrich and various corporate leaders.

Toffler was credited with an idea that the next phase of civilization would be characterized by the pace of change. That is, the people would not only have to adapt to a changing society, but also adapt to a society that was under constant change at a rate that may exceed our ability to keep pace. Technology would advance so quickly that we would not have time to create new habits for the new rules. Instead, we would become corks on a raging river of change.

One of the keys to futurism is to never get too specific about the future, especially the future you expect to see. That way, no one can compare your prediction with what actually happened. Toffler was careful to not get too specific as to what life would be like in a world where the rules changed too quickly for people to adapt. Instead, he imagined a world where some people would be better at coping with constant change and others would struggle, thus creating a new status system.

To some degree this has proven to be true. You see this in the work place where the people rising to the top give off the aura of being infinitely flexible and adaptive, while the people lagging behind end up in accounting. Whether the “highly adaptive” are really adapting to change or striking the needed pose is debatable, but it is something that has become a thing in the corporate world. The highly adaptive are always wise to never ask why something is changing. They just accept it.

In society as a whole, the jury is out. The last decade has been a good test of this new reality and the results are mixed. Obama unleashed a race war in the last two years of his administration that no one saw coming. Then we had the drama of both party primaries in the 2016 elections. No one saw that coming. Trump winning the nomination and then the presidency was a total shock. Then it was four years of chaos and the insane response to the Covid pandemic.

Trump seems like a lifetime ago, yet it has only been a little over a year since he was deposed and replaced with Joe Biden. Five years ago, no sane person thought Joe Biden would ever be president. No one saw the economic chaos that is now starting to define our lives either. We are just scratching the surface on the economic front, as there are a lot of chickens coming home to roost. We are seeing things that not so long ago were declared impossible by the smart set.

There are two conclusions that you can draw from the last decade. One is the public has been remarkably resilient. The middle-class has taken one body blow after another, but has staggered on, not doing much to update its view of society or the people who run the country. This fall, they will dutifully vote for the B-team, who promise to do more of the same, just with better looking performers. The Middle American Radicals remain safely in their pods, munching on their bugs.

The other conclusion is we cannot predict what is coming next. Most people wisely assumed that tomorrow will look like today, with more of the stuff that is popular and less of the stuff that is not so popular. Now, the wise people have to assume that whatever comes next is not being discussed today. If you want to know the future, find a fringe weirdo making crazy claims. Every notable thing that has happened over the last decade was considered aluminum foil hat stuff.

This may be why the Middle American Radicals have been so docile. People need to time to get angry at their rulers and they need something onto which to focus their attention as the main issue. By the time the rulers were willing to tackle inflation in the 1970’s, the people had suffered with it for years. They had time to digest it, understand it and make specific demands about the economy. Reagan won in 1980 largely due to his ability to repeat those demands.

In this age, no one has time to focus on anything very long. We just spent two years having our rights trampled with Covid and it is now on its way to being a conspiracy theory because the new issue is Ukraine. The rage heads on the Left are still struggling to figure out why no one cares about the study of extremism, but that issue was replaced with Covid, which is now being replaced with Putin. Things change so quickly that even the rage heads have no time to get angry.

Of course, the people behind the constant change are living the life of momentary advantage, where they profit from every turn of the wheel. The great transfer of wealth from the middle-class to the over-class is one result. The consolidation of power into the hands of a narrowing elite is another. The new world of constant change is one where the elite can front-run what comes next because they are driving it. Everyone else is left to guess, which means a life of perpetual chaos.

The question no one asks is whether this is sustainable. The consolidation of power may not be by design, but a necessity. At least it is an evolutionary reaction to the accelerating pace of change and uncertainty. Logically, what comes next is some sort of administrative coup where Biden is replaced by the managerial elite. Will that cause a revolt or will it be welcomed? Probably the latter, given what is happening, but maybe that is the point at which the dam breaks.

That is the thing about the world of constant change. No one has time to plan as the rules keep changing. This is especially true of that narrowing ruling elite. They need to keep flipping the pages faster in order to maintain their status, so they can do no long-term planning. Rule by expediency has a history and it is not a promising one, which means it does not have a promising future. The disaster in Ukraine is one example of living in the moment can end in disaster.

What the futurist always get right is that the present modes are running their course and new modes are on the horizon. What they get wrong is that those new modes also come with an expiry date. We may be seeing that with the world Toffler imagined back in the last century. The accelerating pace of change is reaching an end, because mankind can only tolerate so much change. The question is whether it ends in fire or ice, which the poet said would both suffice.

Source:

1. ,https://www.thewrap.com/alvin-toffler-future-shock-author-dies-at-87/

2. Kevin J. Ryan, https://www.inc.com/kevin-j-ryan/4-things-futurist-alvin-toffler-predicted-about-work-in-1970.html

3. https://thezman.com/wordpress/?p=26931