Did you know that the Muslim Persian scholar of medicine, Ibn Sina suspected that some diseases were spread by microorganisms? To prevent human-to-human contamination, he came up with the method of isolating people for 40 days. He called this method al-Arba’iniya (“the forty”).

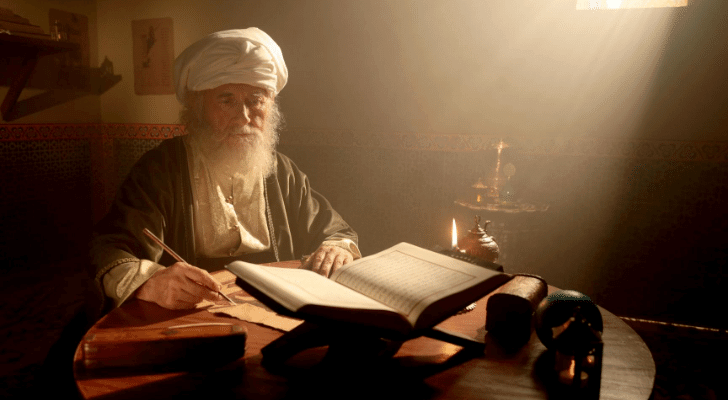

His knowledge of medicine brought to the attention of Nuh ibn Mansur, the Sultan of Bukhara of the Samanid Court, whom he treated successfully. In 997, Avicenna was hired as a physician by Nun ibn Mansur, and he was permitted to use the sultan’s library and its rare manuscripts allowing him to continue his research. This training and the library of the physicians at the Samanid court assisted him in his philosophical self-education. The sultan’s royal library was considered one of the best kinds in the medieval world at the time.

1. Life and Works

Persian philosopher Ibn Sina or Avicenna (c.980-1037) was born in the village of Afshana near the present-day Bukhara (in Uzbekistan) then a leading city in Persia (Iran.) His mother Setareh was from the same village, while his father Abdullah was Ismaili, who was a respected local governor, under the Samanid dynasty was from the ancient city of Balkh (today Afghanistan). His real name is Abu Ali al-Husayn Ibn Abd Allan Ibn Sina, however, he is commonly referred to under his Latinized name Avicenna. In the Muslim world, he is known simply as Ibn Sina.

At an early age, his family moved to Bukhara where he studied Hanafi jurisprudence with Isma‘il Zahid and at about 13 years of age he studied medicine with a number of teachers. At the age of 16, he established himself as a respected physician. Besides studying medicine, he also dedicated much of his time to the study of physics, natural sciences and metaphysics.

His knowledge of medicine brought to the attention of Nuh ibn Mansur, the Sultan of Bukhara of the Samanid Court, whom he treated successfully. In 997, Avicenna was hired as a physician by Nun ibn Mansur, and he was permitted to use the sultan’s library and its rare manuscripts allowing him to continue his research. This training and the library of the physicians at the Samanid court assisted him in his philosophical self-education. The sultan’s royal library was considered one of the best kinds in the medieval world at the time.

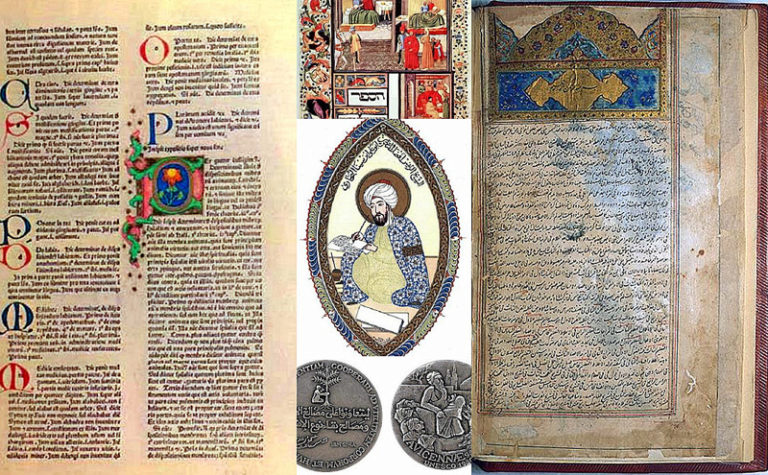

His influence in medieval Europe spread through the translations of his works first undertaken in Spain. In the Islamic world, his impact was immediate and led to what Michot has called “la pandémie avicennienne.” Avicenna wrote his two earliest works in Bukhara under the influence of al-Farabi.

The first, a Compendium on the Soul (Maqala fi’l-nafs), is a short treatise dedicated to the Samanid ruler that establishes the incorporeality of the rational soul or intellect without resorting to Neoplatonic insistence upon its pre-existence. The second is his first major work on metaphysics, Philosophy for the Prosodist (al-Hikma al-‘Arudiya) penned for a local scholar and his first systematic attempt at Aristotelian philosophy.

He later wrote three ‘encyclopaedias’encyclopedias of philosophy. The first of these is al-Shifa’ (The Cure), a work modelled on the corpus of the philosopher, namely. Aristotle, that covers the natural sciences, logic, mathematics, metaphysics and theology. It was this work that through its Latin translation had a considerable impact on scholasticism. It was solicited by Juzjani and his other students in Hamadan in 1016 and although he lost parts of it on a military campaign, he completed it in Isfahan by 1027. The other two encyclopaedias were written later for his patron the Buyid prince ‘Ala’ al-Dawla in Isfahan.

The first, in Persian rather than Arabic is entitled Danishnama-yi ‘Ala’i (The Book of Knowledge for ‘Ala’ al-Dawla) and is an introductory text designed for the layman. It closely follows his own Arabic epitome of The Cure, namely al-Najat (The Salvation). The Book of Knowledge was the basis of al-Ghazali’s later Arabic work Maqasid al-falasifa (Goals of the Philosophers).

The second, whose dating and interpretation have inspired debates for centuries, is al-Isharat wa’l-Tanbihat (Pointers and Reminders), a work that does not present completed proofs for arguments and reflects his mature thinking on a variety of logical and metaphysical issues.

According to Gutas it was written in Isfahan in the early 1030s; according to Michot, it dates from an earlier period in Hamadan and possibly Rayy. A further work entitled al-Insaf (The Judgement) which purports to represent a philosophical position that is radical and transcends Aristotelianising Aristotle’s Neoplatonism is unfortunately not extant, and debates about its contents are rather like the arguments that one encounters concerning Plato’s esoteric or unwritten doctrines. One further work that has inspired much debate is The Easterners (al-Mashriqiyun) or The Eastern Philosophy (al-Hikma al-Mashriqiya) which he wrote at the end of the 1020s and is mostly lost.

When the Sultan of Bukhara, Nuh Ibn Mansour of the Samanid dynasty, became seriously ill, Ibn Sina was summoned to treat him. After the recovery of the Sultan, Ibn Sina was rewarded and was given access to the royal library, a treasure trove for Ibn Sina who read its rare manuscripts and unique books thus adding more to his knowledge.

After the Sultan’s death, and the defeat of the Samanid dynasty at the hands of the Turkish leader Mahmoud Ghaznawi, Ibn Sina moved to Jerjan near the Capsian Sea. He lectured there on astronomy and logic and wrote the first part of his book “Al Qanun fi al Tibb”, better known in the West as “Canon”, his most significant medical work. Later, he moved to Al-Rayy (near modern Tehran) and had a medical practice there.

He authored about 30 books during his stay there. He then moved to Hamadan. He cured its ruler Prince Emir Shams al-Dawlah of the Buyid dynasty from a severe colic. He became the Emir’s private physician and confidant and was appointed as a Grand Viser (Prime Minister).

When Shams al-Dawlah died, Ibn Sina wrote to the ruler of Isfahan for a position at his court. When the Emir of Hamadan became aware of this, he imprisoned Ibn Sina. While in prison, he wrote several books. After his release, he went to Isfahan. He spent his final years serving its ruler Emir Ala al-Dawlah. He died in 1037 AD at the age of 57. He was burried in the city of Hamadan. A monument was erected in that city near the site of his grave.

2. Major Accomplishments

It is claimed that Ibn Sina had written about 450 works, of which 240 had survived. Some bibliographers list only 21 major and 24 minor works dealing with philosophy, medicine, astronomy, geometry, theology, philology and art. He wrote several books on philosophy, the most significant was “Kitab al Shifa” (The Book of Healing). It was a philosophical encyclopedia that brought Aristotelian and Platonian philosophical traditions together with Islamic theology in dividing the field of knowledge into theoretical knowledge (physics, metaphysics and mathematics) and practical knowledge (ethics, economics and politics). Another book on philosophy was “Kitab al-Isharat wa al tanbihat” (Book of Directives and Remarks).

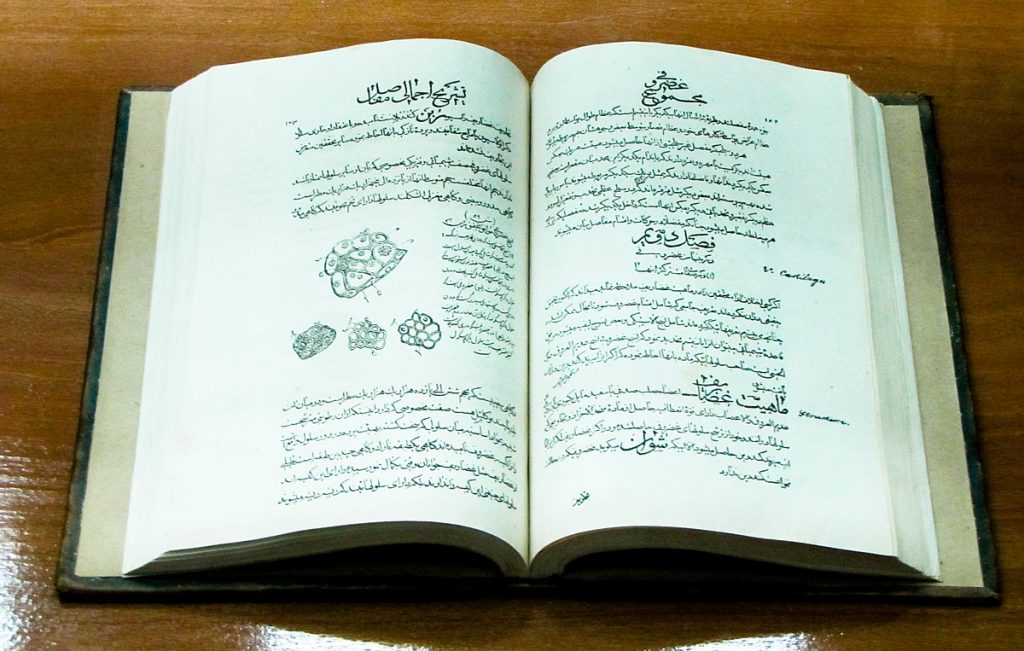

However, his book Al Qanun fi al Tibb or simply the Canon is the most influential medical book ever written by a Muslim physician. It is a one million word medical encyclopedia representing a summation of Arabian medicine with its Greek roots, modified by the personal observations of Ibn Sina. This book was translated to Latin in the 12th century by Gerard of Cremona. It became the textbook for medical education in Europe from the 12th to the 17th century. It is stated that in the last 30 years of the 15th century, the Canon passed through 15 Latin editions and one Hebrew edition. The Canon is divided into five books, including medical therapeutics, with 760 drugs listed. The books are:

-

Book I:

-

Part 1:

The Institutes of Medicine: Definition of medicine, its task, its relation to philosophy. The elements, juices, and temperaments. The organs and their functions.

-

Part 2: Causes and symptoms of diseases.

-

Part 3: General dietetics and prophylaxis.

-

Part 4: General Therapeutics.

-

-

Book II: On the simple medications and their actions.

-

Book III: The diseases of the brain, the eye, the ear, the throat and oral cavity, the respiratory organs, the heart, the breast, the stomach, the liver, the spleen, the intestine, the kidneys and the genital organs.

-

Book VI:

-

Part 1: On fevers.

-

Part 2: Symptoms and prognosis.

-

Part 3: On sediments.

-

Part 4: On wounds.

-

Part 5: On dislocations.

-

Part 6: On poisons and cosmetics.

-

-

Book V: On compounding of medications.

Traders from Venice heard of his successful method and took this knowledge back to contemporary Italy. They called it “quarantena” (“the forty” in Italian). This is where the word “quarantine” comes from. The origin of the methods currently being used in much of the world to fight pandemics have their origins in the Islamic world.

Allah says in the Quran:

Who saves one human life, it is as if he has saved all mankind

Even today Ibn Sina’s method saves thousands, perhaps millions, of lives.

Source:

1. https://iep.utm.edu/avicenna/

2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6077049/

3. https://www.ediblewildfood.com/bios/ibn-sina.aspx